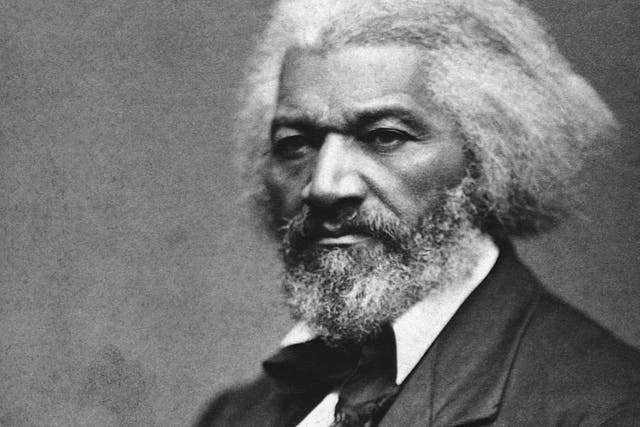

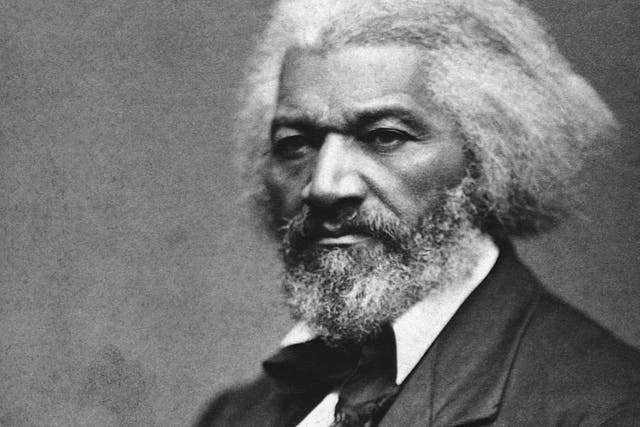

Frederick Douglass was a formerly enslaved man who became a prominent activist, author and public speaker. He became a leader in the abolitionist movement, which sought to end the practice of slavery, before and during the Civil War. After that conflict and the Emancipation Proclamation of 1862, he continued to push for equality and human rights until his death in 1895.

Douglass’ 1845 autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, described his time as an enslaved worker in Maryland. It was one of three autobiographies he penned, along with dozens of noteworthy speeches, despite receiving minimal formal education.

An advocate for women’s rights, and specifically the right of women to vote, Douglass’ legacy as an author and leader lives on. His work served as an inspiration to the civil rights movement of the 1960s and beyond.

Frederick Douglass was born into slavery in or around 1818 in Talbot County, Maryland. Douglass himself was never sure of his exact birth date.

His mother was an enslaved Black women and his father was white and of European descent. He was actually born Frederick Bailey (his mother’s name), and took the name Douglass only after he escaped. His full name at birth was “Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey.”

After he was separated from his mother as an infant, Douglass lived for a time with his maternal grandmother, Betty Bailey. However, at the age of six, he was moved away from her to live and work on the Wye House plantation in Maryland.

From there, Douglass was “given” to Lucretia Auld, whose husband, Thomas, sent him to work with his brother Hugh in Baltimore. Douglass credits Hugh’s wife Sophia with first teaching him the alphabet. With that foundation, Douglass then taught himself to read and write. By the time he was hired out to work under William Freeland, he was teaching other enslaved people to read using the Bible.

As word spread of his efforts to educate fellow enslaved people, Thomas Auld took him back and transferred him to Edward Covey, a farmer who was known for his brutal treatment of the enslaved people in his charge. Roughly 16 at this time, Douglass was regularly whipped by Covey.

Black Leaders During ReconstructionAfter several failed attempts at escape, Douglass finally left Covey’s farm in 1838, first boarding a train to Havre de Grace, Maryland. From there he traveled through Delaware, another slave state, before arriving in New York and the safe house of abolitionist David Ruggles.

Once settled in New York, he sent for Anna Murray, a free Black woman from Baltimore he met while in captivity with the Aulds. She joined him, and the two were married in September 1838. They had five children together.

After their marriage, the young couple moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts, where they met Nathan and Mary Johnson, a married couple who were born “free persons of color.” It was the Johnsons who inspired the couple to take the surname Douglass, after the character in the Sir Walter Scott poem, “The Lady of the Lake.”

In New Bedford, Douglass began attending meetings of the abolitionist movement. During these meetings, he was exposed to the writings of abolitionist and journalist William Lloyd Garrison.

The two men eventually met when both were asked to speak at an abolitionist meeting, during which Douglass shared his story of slavery and escape. It was Garrison who encouraged Douglass to become a speaker and leader in the abolitionist movement.

By 1843, Douglass had become part of the American Anti-Slavery Society’s “Hundred Conventions” project, a six-month tour through the United States. Douglass was physically assaulted several times during the tour by those opposed to the abolitionist movement.

In one particularly brutal attack, in Pendleton, Indiana, Douglass’ hand was broken. The injuries never fully healed, and he never regained full use of his hand.

In 1858, radical abolitionist John Brown stayed with Frederick Douglass in Rochester, New York, as he planned his raid on the U.S. military arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, part of his attempt to establish a stronghold of formerly enslaved people in the mountains of Maryland and Virginia. Brown was caught and hanged for masterminding the attack, offering the following prophetic words as his final statement: “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.”

John Brown's Harpers FerryTwo years later, Douglass published the first and most famous of his autobiographies, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. (He also authored My Bondage and My Freedom and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass).

In it Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, he wrote: “From my earliest recollection, I date the entertainment of a deep conviction that slavery would not always be able to hold me within its foul embrace; and in the darkest hours of my career in slavery, this living word of faith and spirit of hope departed not from me, but remained like ministering angels to cheer me through the gloom.”

He also noted, “Thus is slavery the enemy of both the slave and the slaveholder.”

Later that same year, Douglass would travel to Ireland and Great Britain. At the time, the former country was just entering the early stages of the Irish Potato Famine, or the Great Hunger.

While overseas, he was impressed by the relative freedom he had as a man of color, compared to what he had experienced in the United States. During his time in Ireland, he met the Irish nationalist Daniel O’Connell, who became an inspiration for his later work.

In England, Douglass also delivered what would later be viewed as one of his most famous speeches, the so-called “London Reception Speech.”

In the speech, he said, “What is to be thought of a nation boasting of its liberty, boasting of its humanity, boasting of its Christianity, boasting of its love of justice and purity, and yet having within its own borders three millions of persons denied by law the right of marriage?… I need not lift up the veil by giving you any experience of my own. Every one that can put two ideas together, must see the most fearful results from such a state of things…”

When he returned to the United States in 1847, Douglass began publishing his own abolitionist newsletter, the North Star. He also became involved in the movement for women’s rights.

He was the only African American to attend the Seneca Falls Convention, a gathering of women’s rights activists in New York, in 1848.

He spoke forcefully during the meeting and said, “In this denial of the right to participate in government, not merely the degradation of woman and the perpetuation of a great injustice happens, but the maiming and repudiation of one-half of the moral and intellectual power of the government of the world.”

He later included coverage of women’s rights issues in the pages of the North Star. The newsletter’s name was changed to Frederick Douglass’ Paper in 1851, and was published until 1860, just before the start of the Civil War.

In 1852, he delivered another of his more famous speeches, one that later came to be called “What to a slave is the 4th of July?”

In one section of the speech, Douglass noted, “What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy—a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages.”

For the 24th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, in 1886, Douglass delivered a rousing address in Washington, D.C., during which he said, “where justice is denied, where poverty is enforced, where ignorance prevails, and where any one class is made to feel that society is an organized conspiracy to oppress, rob and degrade them, neither persons nor property will be safe.”

During the brutal conflict that divided the still-young United States, Douglass continued to speak and worked tirelessly for the end of slavery and the right of newly freed Black Americans to vote.

Although he supported President Abraham Lincoln in the early years of the Civil War, Douglass fell into disagreement with the politician after the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, which effectively ended the practice of slavery. Douglass was disappointed that Lincoln didn’t use the proclamation to grant formerly enslaved people the right to vote, particularly after they had fought bravely alongside soldiers for the Union army.

It is said, though, that Douglass and Lincoln later reconciled and, following Lincoln’s assassination in 1865, and the passage of the 13th amendment, 14th amendment, and 15th amendment to the U.S. Constitution (which, respectively, outlawed slavery, granted formerly enslaved people citizenship and equal protection under the law, and protected all citizens from racial discrimination in voting), Douglass was asked to speak at the dedication of the Emancipation Memorial in Washington, D.C.’s Lincoln Park in 1876.

Historians, in fact, suggest that Lincoln’s widow, Mary Todd Lincoln, bequeathed the late-president’s favorite walking stick to Douglass after that speech.

In the post-war Reconstruction era, Douglass served in many official positions in government, including as an ambassador to the Dominican Republic, thereby becoming the first Black man to hold high office. He also continued speaking and advocating for African American and women’s rights.

In the 1868 presidential election, he supported the candidacy of former Union general Ulysses S. Grant, who promised to take a hard line against white supremacist-led insurgencies in the post-war South. Grant notably also oversaw passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1871, which was designed to suppress the growing Ku Klux Klan movement.

In 1877, Douglass met with Thomas Auld, the man who once “owned” him, and the two reportedly reconciled.

Douglass’ wife Anna died in 1882, and he married white activist Helen Pitts in 1884.

In 1888, he became the first African American to receive a vote for President of the United States, during the Republican National Convention. Ultimately, though, Benjamin Harrison received the party nomination.

Douglass remained an active speaker, writer and activist until his death in 1895. He died after suffering a heart attack at home after arriving back from a meeting of the National Council of Women, a women’s rights group still in its infancy at the time, in Washington, D.C.

His life’s work still serves as an inspiration to those who seek equality and a more just society.

Watch acclaimed Black History documentaries on HISTORY Vault.

Frederick Douglas, PBS.org.

Frederick Douglas, National Parks Service, nps.gov.

Frederick Douglas, 1818-1895, Documenting the South, University of North Carolina, docsouth.unc.edu.

Frederick Douglass Quotes, brainyquote.com.

“Reception Speech. At Finsbury Chapel, Moorfields, England, May 12, 1846.” USF.edu.

“What to the slave is the 4th of July?” TeachingAmericanHistory.org.

Graham, D.A. (2017). “Donald Trump’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass.” The Atlantic.

HISTORY.com works with a wide range of writers and editors to create accurate and informative content. All articles are regularly reviewed and updated by the HISTORY.com team. Articles with the “HISTORY.com Editors” byline have been written or edited by the HISTORY.com editors, including Amanda Onion, Missy Sullivan, Matt Mullen and Christian Zapata.